Speaker Key

Q: Pre-written question

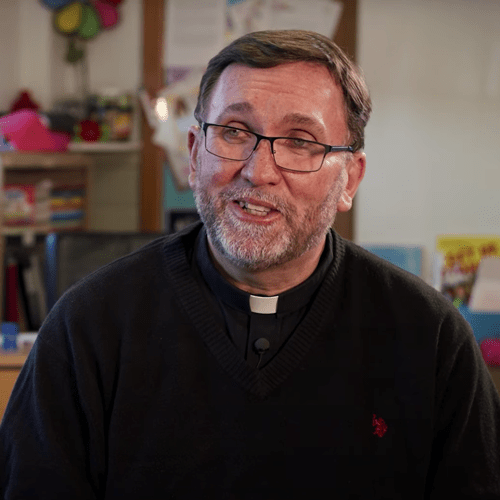

R1: Father Mike Russo

I1: Father Chris

I1: I think as we minister to not only to an increasingly non-white church, but also a church that has very different experiences as far as socio-economics and political experiences, I think the challenge is diverse and the willingness to sort of what the church has done when it’s been its best all throughout history, meet people where they are, understand their needs, and then preach the gospel to them. I think that’s a method that Christ himself gave us 2,000 years ago, and again the expression has been used often that the movement from maintenance to mission.

Our motto at St. Raymond’s is; “At St. Raymond’s Church—where God is glorified and his people are sanctified” and at the end of each day as I reflect on my day, I ask God forgiveness for the times I didn’t glorify him and for the times that I didn’t take advantage of being sanctified, but most of the time I am just thanking God for the opportunities where I glorified him with others in worship and also experienced sanctification through my gift of self and sanctification through the other people who as many other priests will say, it’s the people of God who call us to be holy. They call out of me, this call to be the man of God that they need me to be and that God needs me to be.

R1: Our Preacher journey takes us to Mount Airy, a northwest neighborhood of Philadelphia. We are here to meet Father Chris Walsh the pastor of St. Raymond Penafort Catholic Church. Father Chris’ embrace of this African-American community brought his next door neighbors into the church. Helped educate children in the parish school and built a bridge for community service and identity in Africa. With his gift of preaching and pastoral zeal, Father Chris transformed this tiny section on Philly. They tell me this is a place where God is glorified, and his people sanctified. Let’s meet Father Chris Walsh.

We are here in the first grade classroom at Saint Raymond’s school. Father Chris, it’s great to be here.

I2: Thank you so much, Father Mike. Welcome to Philadelphia and welcome to St. Raymond’s.

R1: Well, recently with the death of Toni Morrison, the great Nobel Prize winning author, she wrote this in 2004; “I know the world is bruised and bleeding, though it is important not to ignore its pain, it can lead to knowledge, even wisdom.” She goes on to say this; “Like art, this is precisely the time for artists to go to work. There is no time for despair, no need to silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. This is how civilizations heal.” I am curious—I always think that preaching is an art form. I am wondering from you, how has your preaching brought about healing and even racial healing in this community?

I2: It’s been a great joy of doing pastoring here for 12 years. It took a little while to get to know the people and their own experiences of life. Certainly, their own experiences of racial division, their own experiences with the church, their own experiences with broken marriages and broken families and hurts and pains that we all carry with us. I do think that’s a part of my mindset when I am preaching. Christ was the healer. So, if we are going to continue the ministry of Christ, I think bringing his healing presence alive in the word proclaimed and the word preached is essential for people’s lives. So, I think trying to build that bridge as I preach, aware of the wounds, the many diverse and real and sometimes very profound and deep wounds that people have from being hurt by another person. Bring them to a place where they can acknowledge that—I love the gospel image where Jesus asks the man with the withered hand to come up in front of everyone and extend it. I often think he probably never showed that part of his woundedness, that part of his brokenness to anyone. Yet, when we encounter Christ, he wants us to say yes, I am wounded, because its only when we admit that, that we can then experience the healing. So, through preaching, making it okay—as I share my own wounds with people, my own fears, my own pains—then show them how to bring them to Christ and move forward to become the women and men that he desires us to be.

R1: You came here twelve years ago. How did you have to adjust as a white priest in an African-American church?

I2: Yes. I came really humbly—as humbly as I can be. Admitting that this was a different place. I had five years at my first assignment, which was another section of Philadelphia. Then, I was teaching high school for four years. So, preaching mostly to young people—even on weekends at a life teen mass on Sunday nights. So then stepping into a parish community in a neighborhood where I had never lived, with a vastly majority African-American and African and grew up in an American community—I needed to know their stories. Needed to know the language that was appropriate. I needed to know the style that they were used to—the call and response and what they desired. So, it became really a matter of study. Of reading books, of watching black preachers who were very effective—of getting feedback from people as to what was working and maybe what wasn’t.

R1: What are the key ingredients in that kind of black preaching?

I2: I think they would be filtered through my own experience. So, I think that was something somewhat new for me in being more vulnerable with my own struggles, with my own experiences of God and God’s grace and sharing what God was doing in me. Of figuring out the call and response of when to solicit an amen. Of what worked with this community that might not work in another community as well because certainly not every black church or black Catholic church is the same. So, it was just the willingness to try things, to ask for feedback, and to be willing to make mistakes as I move forward as a preacher here.

R1: So, there are 3 million African-American Catholics in the United States. Often enough, black Catholics have struggled with their own identity to be authentically black and truly Catholic. How do you see that divide?

I2: You know, the parish exists on the edge of the city, so we are sort of the last line before the city goes into the suburbs. So, many of our parishioners live outside of the neighborhood, but when they go to their local parish, they don’t have the experience of church that they are looking for, so they come back. There is something different. When non-African-Americans come here to worship, they get a sense of that. So, many of them come and they experience it as well. I think the three ingredients that make for an authentically black and authentically Catholic church are similar to what is happening in parishes that are vibrant across the country. Music, and certainly the black church has its own experience of music and we have been very blessed with two amazing choirs and a variety of cantors who can bring that not only great tradition of gospel music, but also contemporary gospel music as well in a way that really touches the soul and allows the person to be emotive. So, if they want to stand, if they want to raise a hand, if they want to sway, if they want to get in the aisles and move, they are free to do that. Where certainly in some other parishes the usher might come and think they were having a seizure and walk them out. I think secondly, the way the word is preached, that my folks are not always looking for a five minute homily, but they don’t mind the word being broken open and applied to them and given an opportunity to digest it and identify with it. Lastly, just the experience of fellowship. I think it’s part of the black church experience going back to the time of slavery where you know, Sunday was a day away from the experience of the oppression of slavery and so they were often spending the day together. Their true identity was being lived out, so again allowing opportunities for people to come early, to come late, to stay later, and to fellowship with one another and to really get to know each other.

When I first got here, I learned an expression that was kind of new to me, the “church family”. I had never heard that in any parish where I had lived, or I had served. It’s kind of struck me strange but very quickly after arriving in Saint Raymond’s it became very clear that not only was there a great desire for this to be a family, to share the joys and sorrows, to support one another in times of grief and joy, but it was really being lived out. It wasn’t just spoken about. That there really was a sense of genuine care for each other and wanting to celebrate the milestones of life together. Because we are a smaller community, that also makes that possible as people get to know each other and walk alongside each other in life.

R1: What is your thinking about outreach and evangelization to youth?

I1: One of the great joys of being pastor at St. Raymond’s is that our parish school is still open through the partnership with many wonderful organizations and I remember as a child the parish priest coming into the classroom teaching us different things, being lighthearted. I think in many ways that’s part of the way my own vocation to the priesthood was born. So, I have always tried to be present in the school. I think at St. Raymond’s where the vast majority of the students in our school are not yet catholic, it plays an added role in I want to have a positive relationship with the students so that I can then develop a positive relationship with the parents so that I can then invite them to come worship with us. We are pretty intentional about our outreach in the school and because the vast majority of our students don’t know Christ, they don’t know God. It’s not that they are worshipping in some other church, they are not worshiping anywhere on Sunday morning. So, not using the relationship with the students, but allowing the relationship to lead hopefully to a relationship with Christ.

So many of our African-American Catholics had their conversion experience either because their children were in a catholic school or they themselves were in a catholic school. So, we don’t tire asking, even despite all of the problems that the church is facing today, the many challenges that are very, very real in the church, we don’t stop inviting. We don’t stop asking. That includes here among children in our school.

I think a vast majority of young people have just never had an experience of God. Even if they were church goers at one point, they have never had an experience of meeting God in the service of a person who is poor or suffering. They have never experienced God in feeling of His presence in eucharistic adoration or in some great retreat experience. They have never learned how to pray. So, I think one of the things we have tried to do here at St. Raymond’s, and I am certainly trying to do at the high school, is give young people those experiences. Whether it’s through retreats, or service opportunities. The other thing is to expose them to as many adults as possible. Some years ago, I read a research project done by the evangelical world that if teenagers had seven adults in their life who were living as disciples of Christ—seven adults other than their parents—then they were more likely to identify as a Christian when they became an adult themselves. So, rather than having just the youth minister being the only one who interacts with young people, having lots of people, lots of people in the parish community who are trying to have those interactions, to share their own stories of what difference God has made in their life.

R1: So, when you think of racial healing, I often go back to Archbishop Desmond Tutu and the TRC, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. With our own present political divides in the United States and disorder in places like Ferguson or Charlottesville, you name the city—Baltimore, Oakland—as a community leader here in Philadelphia, what is your formula for this city and your people, how you chart progress despite sometimes loud and often costly setbacks?

I2: I think prior to my being appointed to pastor at St. Raymond’s, if someone had asked me is racism real in America, I probably would have said you know, it’s there, but its small, it’s very few people. But, after 12 years, we are still a very segregated society. Where I see that especially is at funerals. If the deceased is African-American, the vast majority, 99% of the people in the pews are black. If the deceased is a white person, 99% of the people in the pews are white. I think that’s very telling. Right? When someone dies, who were their close friends? Not who do they know, but who are their close friends? It has just become apparent to me, now there are people in our community, which is racially mixed – when they die, they do have a great representation of people of different races and cultures that are here, because that was the way they lived their lives. But, the vast majority of people it seems live a pretty segregated life. I have also witnessed firsthand the things that people say to me. You know, oh, it’s a black parish must be difficult financially. The assumption, because it’s a black parish—you know—we don’t have money to pay our bills. Which is not the case, but the presumptions that come, the prejudgment, the prejudice that comes. Having been with my parishioners in different settings and experienced slights by a hostess of a restaurant or someone in a public setting. So, it is real. Certainly, when there were the shootings in Charleston or Ferguson, we have joined in prayerful witness, but one of the expressions that I have used a lot is that prayer is good, but prayer is not enough. That the Lord is calling us to action. With other black catholic churches here in Philadelphia, we have tried to engage in some conversations around race. Particularly around the birthday of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King. So, we have gone to mostly white suburban parishes and had those conversations and there has been some fruit from them. Some understanding. We are looking to sort of continue that dialogue because it’s not just on the racial issue, but it’s on the immigration issue, it’s on the gun control issue, where people are increasingly polarized within the church. So, here we are, we want to proclaim that we are one in Christ and that we are one body in Christ, and yet there is great division on issues and so I think coming to some understanding of how these issues affect other people within the body of Christ would be key. I don’t see that conversation happening at the national level or even being led at the diocesan level at this point, I hope that it one day would. So, I think continuing to try and have small conversations first and foremost within the parish and then taking it maybe to other parishes at other churches to have that conversation is certainly in our heart. I don’t know how to measure success there because I think that it’s the conversion of heart. One individual at a time and trying to raise that awareness that we heal some of the real pains within our church. I think another way of doing that is raising up some of the individuals from the black community who are being held up for canonization. Father Tolton, who experienced horrible racism. He wasn’t even able to go to a seminary in America – he had to go to Rome. Then when he came back, he experienced great difficulty out in Illinois. So many others – Mother Lang, Henriette Delille, who lived these beautiful lives. I think it’s one of the ways that hopefully the larger church can engage at some level on the experience of racial prejudice that is part of the church history. I have many parishioners who have been denied communion and not in distant times, but you know because they are in a mostly white church and they go up for communion and the Eucharistic minister or sometimes the priest has said, “Are you Catholic?” “Yes, that is why I am in line.” Those types of things. Or, others being told perhaps you would feel more comfortable at another parish like St. Raymond’s. Well intentioned, no doubt, but not understanding the gravity that comes with a comment like that.

R1: So, one last question—give us a preview about tomorrow. What are we going to see, what are we going to hear, and who is coming?

I2: Yes, well who is coming? That’s always the great question for pastors. We have a variety of folks who come, many are folks who live in the neighborhood, others who have moved out of the neighborhood but still come back to worship. We just have people who sometimes I refer to as the friends of St. Raymond’s who for lots of different reasons that this period of their life are worshiping with us. That may continue, they may move on to other communities. The gospel this weekend has Jesus asking the question–I am sorry, the disciples making the demand of Jesus—increase our faith. So, we are going to talk about faith can animate us, hopefully. How it can lead to a relationship with Christ to transform us. It’s difficult because as a preacher like most preachers, I preach every Sunday to three different masses with three kind of different communities. They are all the folks from St. Raymond’s but they are folks who want to worship in a different way and so while the message is the same, it certainly becomes proclaimed and animated in very different ways so that the people of God can hear the message the way they need to hear it.

In Matthew’s gospel, he says if you have got faith the size of a mustard seed, you will be able to say to the mountain, be moved. Let these things sink in. A tree. Be uprooted. Right? This time of year, you say be uprooted and be planted on my neighbor’s yard, so the leaves fall there. Right? But same the mountain, be uprooted and be moved. Now, some scholars say that Jesus is sort of poking fun at the disciples. Because they have got this idea that faith is about being able to do really extraordinary things. Right before this, the disciples had asked Jesus that they have the ability to call down fire on anyone who rejected them. Let’s admit it, that would be pretty cool. Right?

What Jesus is saying to us, to his disciples, right, if you really want to have faith it’s not about calling down fire. It’s not about doing all sorts of extraordinary things or getting people to look at you. But rather, serve your spouse. Serve your kids. Serve your parents. Serve the neighbor who is in need. Serve the stranger who needs a little help. Take care of the other person and do it in a way that you are not looking for attention. You are not looking for recognition. You are not looking to be noticed. That is how real faith is lived out because real faith, even when it’s very, very small, puts us in a relationship with God. Right? It’s not about power. It’s not about the power or abilities to do this, it’s not even about the healings that, praise God, takes place for many of the disciples. But faith is what puts us in a relationship with God when we realize that is how we are going to be changed. That’s how we are going to become the women and the men that we are meant to be when we are in relationship with him.

R1: At the 12 noon mass we will have a special group?

I1: Yes, Sunday afternoon this is our once a year gathering for Catholics of African heritage mostly folks, who have lived in Kenya or any of the—Sierra Leone and Cameroon and Togo and Nigeria and have moved to Philadelphia and then they have their own masses throughout the year, but once a year all come together.

So, it’s just a great joy each week to have a group of people who come wanting to praise God, wanting to worship God, but also wanting that worship to transform their lives so they can go back into the world and be the presence of Christ for others.

R1: Mother Katherine Drexel, a sister of the blessed sacrament transferred her vast family fortune into a brace for the care and education of African-American and Native-American communities around our country. In addressing the task, the saint once observed; “If you wish to serve God and love our neighbor well, we must manifest our joy in the service we render to him and them. Let’s open wide our hearts. It is joy that invites us. Press forward and fear nothing.” I want to thank Father Chris Walsh and the parishioners here at St. Raymond’s for their assistance and all their efforts on behalf of the preaching ministry. In Philadelphia, and for Sunday to Sunday, I am Father Mike Russo.