Speaker Key

FM: Father Mike Russo

l1: Father Ricky

Intro: I think a one word term that comes to mind is balance. Drawn from Taoism, I think there is an integrated whole, and so I look at my own life as being a life that continually tries to balance the various aspects from spirituality to health, to ministry, to being open to God’s will.

R1: I am here at Old St. Mary’s Cathedral in the heart of San Francisco’s ChinaTown. I am here to meet Father Ricky Manolo. Such a historic setting. This is California’s first cathedral church built in 1853. Only three years after California became a state. The cathedral’s foundations withstood the 1906 earthquake and it’s here where the Paulist Fathers created the very first Catholic Chinese Mission. Father Ricky is a Paulist priest, composer liturgist, and someone well equipped to explain the religious roots of the Asia-Pacific community and how the church may best preach, inform us into a people of mercy and grace.

I am here at the Paulist Center on Grant Street with Father Ricky Manolo. Welcome.

I1: Thank you Mike, great to be here.

R1: The British essayist Walter Pater once said a century ago that all art conspires to the condition of music. All art aspires to the condition of music.

I1: I love it.

R1: So, in this case, where you have both preaching and music, which are both art forms, how does your music inform your preaching and how does your preaching inform your music?

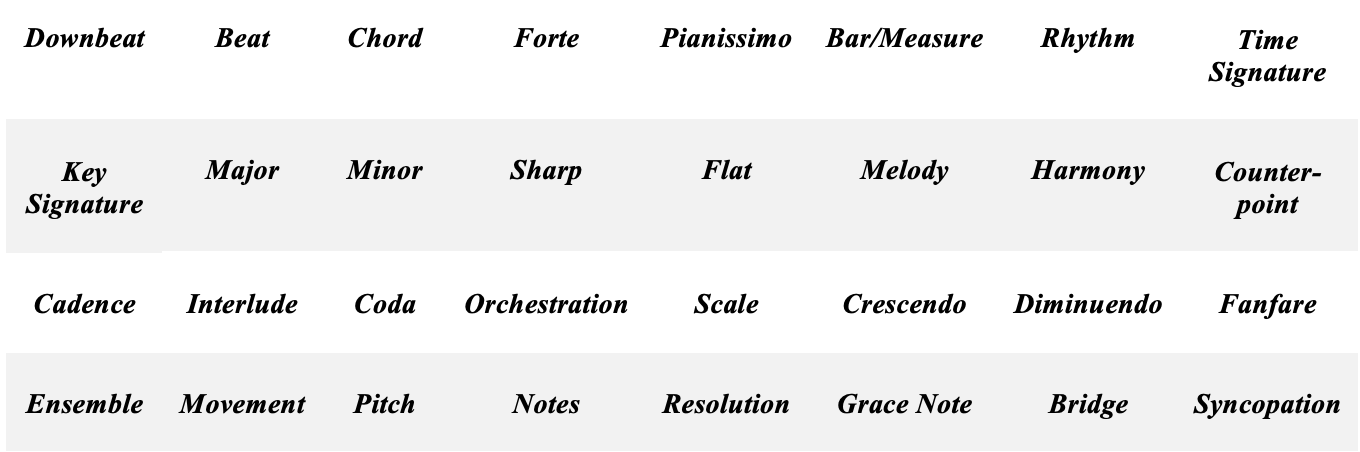

I1: A great deal. A great deal. Usually when I prepare a homily, I actually employ the same tools and you know, devices and imaginations that I do with music, with my homilies and all of that. So, for example, when I compose a piece, a song, or symphonic work, whatever it may be, there is a particular structure there. There is a rhythm. There is a flow. There is an introduction, there is an ending. I do the same thing with my homilies. There’s an introduction. There is a point. There might be a peak, per se. I am very mindful of the actual structure of a homily within a particular time slot, within a particular ritual moment. I think I might look at theme and variations. I might look at engagement. What are the points when I want people to come into it? What are the particular motives and how do I develop that? So, all of that really comes into play. The difference of course is music is a sonic experience, that you mentioned, right? But, then I think any ritual moment during liturgy is also its own event with a beginning and an end. Some of us connect it to a larger structure, so I think my musical background gave me the I guess abilities to be able to see those differences.

R1: One of the things I discovered in doing some research is that you and I both have a passion for Steven Sondheim.

I1: I am like an honorary—

R1: Actually, I borrowed his lyrics to be a springboard for several of my homilies. But, I want to ask you this one thing; has musical play, Pacific Overtures, greatly influenced your composition of Many and Great?

I1: What Sondheim taught me was how to use and employ maybe particular musical motives, but don’t overuse it. You know, he was influenced by one of his teachers, Milton Babbitt. Wonderful classical composer. I met Sondheim once actually and I asked him what did Milton Babbitt teach you? He said well, he taught me how to look at any particular musical motive, it might be a melodic motive, it might be a lyrical motive but don’t overuse it. You know, what Milton Babbitt taught Sondheim would eventually lead to one of Sondheim’s dictums—less is more. You know, and Milton Babbitt would kind of teach Steven Sondheim—he would look at a Bach fugue and look at maybe four notes that Bach used and how Bach was able to turn these four notes into this–what he would say a cathedral. I see similarities also in homiletics. I would use that same thing. How do we use perhaps one particular theme? How do we develop it, not over use it? I recall Bishop Ken Untener. One of his I guess in his book “Better Preaching” he talks about how in preaching he should make one point but make it deep. I think that is what Sondheim was referring to when he was talking about Milton Babbitt. Rather than use too many—put too many eggs in one basket how do we actually lead the listener or in a mass setting, the liturgical assembly, how do we lead them into recognize this one motive that is going to be somehow, hopefully, the preacher is able to put that into a deeper invitation for them to understand the theme.

R1: So Many and Great uses the pentatonic scale.

I1: Yes.

R1: That is definitely an influence that comes from the Pacific. So, the Pacific Overture is something we are looking at, particularly with your own ministry?

I1: Yes, so there is an example. It was my first song where I used a pentatonic scale. Five note scale, as opposed to the classical European classical eight note scale or 12 notes system. Because it’s only five notes, you are able to enter into the song without too many superfluous or elements going on. You know, so but even then I was also influenced by Japanese cinema.

R1: Kurosawa?

I1: Absolutely. You know, again there is a very minimalist approach to some of the things he did. It would have this opening scene let’s say in Seven Samurai and you would see this wonderful field out there and nothing is happening. Unlike most American summer shows where there is always action that is needed, but then that one moment you then might actually see like a horseback rider approaching somewhere. So, it’s kind of causes us to just be aware of what is going on. Be mindful of the surroundings, the context. Allow the context and the scenery to sort of open up. That’s the same thing with my song, Many and Great. Only five notes, well I mean I go in different ranges within those five notes, but by the end of the first verse, so the refrain—actually by the end of the verse, the people already have all of the musical motives there. Which is very telling of a lot of Sondheim musicals. You know, like he would say the opening song of many shows should be the exposition. Like “Into the Woods” by the end of that opening song you have all of the—

R1: You know where you are.

I1: Yes, you already know the musical motives that are going to be employed throughout the whole musical. You have the four stories, four main storylines that are going to be kind of unfolding and I think that should you know, for me at least, that is how I use those tools for shaping a homily.

R1: Sure.

I1: How does the opening give an exposition to what is to follow?

R1: And always these can spark your own imagination.

I1: Exactly, yes. I think you can build upon that. You know, or maybe at the end there could be an arch back to that. So, there is always that is—again, that’s how my mind thinks because of music, I am always conscious of the actual structure, the shape, the form, all of that. How is it all being employed? In this case, within eight to twelve minutes.

R1: Let’s come back to Pacific Overtures for a moment. So much of your ministry has looked at the Pacific and it’s the largest metaphor we have geographically right, in terms of the size and the diversity of cultures? I think the thing that most encourages me about our conversation is that you have tried to have a way of entering into that language, texts, the people but it’s so diverse. Where do you begin?

I1: That is a very good question. It’s very difficult to know where to begin because I was born in Brooklyn and so I was both Asian with my Filipino and my grandfather was Chinese identity. But I was also very mainstream US culture. You know, as far as that identity. So, when I was thinking about I guess when I wrote Many and Great—when I was thinking about well how might I be able to contribute you know, or bring to the repertoire in many Catholic parishes here in the United States, how might I be able to introduce them to an “Asian culture”. Like you said, there are just as many identities there—more so than a lot of other you know, terms we use, when it comes to identity. That is why I began to employ the idea of the pentatonic scale. Not every Asian culture uses that musically, but a lot of east Asian cultures do, like Vietnamese culture, Chinese, and Japanese. They might use that pentatonic scale.

R1: So how do we unleash the treasures that are in these cultures, right? Listen more carefully to the rich treasures that are there, be able to use them for the church nationally and globally?

I1: Well, I think we first have to be a listener and you have to be a part of that culture and you have to enter into that culture with some kind of earnest or intentionality to be able to learn from them. It’s not just a matter of I am going to go into a Japanese culture like I did with “Many and Great” and then just kind of take anything I want—appropriate—colonize them. You know what I am saying?

R1: Yes.

I1: So, one of the questions you have to ask is to what extent can I first be a learner, a listener, a partner with them rather than over them, but sort of be side by side. What can you teach me about my music? That is what I did with my own music. How might you actually immerse yourself in that culture, be part of it. Before I began my doctorate degree at Berkeley, I lived in China for two years and I traveled all over Asia, knowing that I was going to have a particular focus on Asian Catholicism. I felt like I needed to actually live there rather than go fly over and they say give me what you got, per se. So, but once you have that disposition, then the actual gifts kind of emerge. I don’t look for them. You have dialogue with them. There might be something that might be a particular question I have in mind, but you sort of allow the spirit to work through them and then present those gifts.

R1: There is an interreligious aspect to this too.

I1: Very much so.

R1: Because Catholicism is such a minority in some of these countries.

I1: It is outside of the Philippines. You know? It is. So, even then you have to kind of recognize that already that I am coming in as a minority with my own collar or my own Roman Catholic sensibilities with which I grew up.

R1: Now here in San Francisco and not so many miles away is San Jose and a very large and robust Vietnamese community. I remember a few years ago there was a debate within that community as to whether to name the section of San Jose—it was either going to be Little Saigon versus the Vietnamese Business District. It was a fierce fight and it betrayed a lot of the political and cultural tensions that are present within that community. How do you hear that clearly and be able to pastorally address those who want to adapt and maybe others who are reluctant to adapt?

I1: You know, again the preliminary question is how am I part of that community. Am I immersing myself? Am I going to their gatherings? It might be in their homes at prayerful gatherings, they might have other gatherings outside of the church. How do I listen to their stories? I think the narrative approach is really the most important piece. Sometimes pastoral leaders you know, they only think about questions that are raising only at the time when they have to come up maybe with a homily or maybe in my case it might be a particular song which I might want to bring in. That’s the time I—well actually that ought to be going on before these particular projects.

R1: When I am usually called in, it’s when the crisis hits.

I1: That is exactly what happens. So, I usually suggest start doing that now. Know who the key doorkeepers are to various culture groups. Start immersing yourself. When someone invites me to perhaps baptize their child or somebody—one of the things I say is well let’s have dinner. I want to go to your home. I want to find out. I want to know your cultural context first. That usually surprises them. Because they themselves think that they are just going to bring their baby and then pop—I am going to know all about them. Well no, I want to be able to weave that into my homily, into the way I preside, what might I learn from you, what are your stories. So, I might not wait until the funeral –all Asian cultures, Asian Pacific island cultures are collectivists. They are very communitarian, so they really pride themselves with being intrinsically connected and having some kind of accountability to all members, but particularly the older, per se. Whereas here, US mainstream culture, we kind of champion individualism. So, when it comes to any kind of ritual it’s right away going to be everyone. Everyone that is there, present, and not just an individual choice, but they have a lot of value or place a lot of value in how everyone is connected to this event.

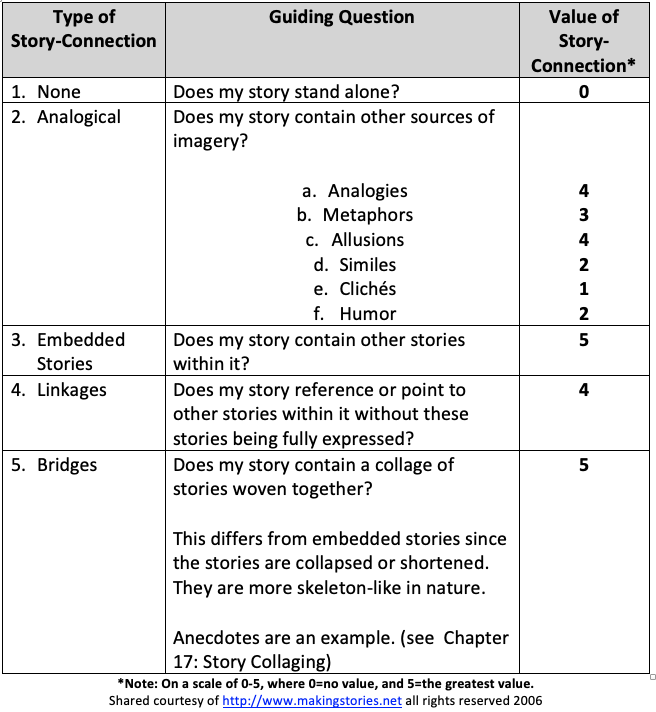

R1: So, this idea of adapting and understanding carefully the community that you are serving brings us to a topic that you have written about. Contextual preaching. You call it a pastoral imperative. What do you mean by contextual preaching?

I1: Well, I wrote this chapter with Steven Bevins and we were asked to write a chapter in the book about preaching on preaching and culture. When I met with Steven we had preliminary thoughts about it, but then Steven at one point said well, it’s not—it’s more than just culture as a whole context there. What he was talking about, which he is a guru when it comes to contextual theology, is that culture might be a particular community’s identity, the rituals, symbols, values they might have, but sometimes there are other events in the life of a community that go beyond those symbolic rituals or symbols, or even music or all of that. There might be a natural disaster that just happened let’s just say a week before. So, when it comes time for preaching, you can’t ignore that. You have to bring that into—you have to bring that into somehow into the homily or at least within the mass, prayers of the faithful, whatever it may be, because that is what is going on in the lives of the people. So, we coin that term contextual preaching as you were saying, a pastoral imperative, because the preacher has to know the larger social context that goes on outside of the four walls of a church building. It might be a contextual situation that the preacher is going through. It might include my own cultural values, but it’s not limited to the culture. It might be something going on that everybody knows about, that might be an ecological crisis for example. So, I believe one of the tasks of preachers is to be able to be a mediator between their lived Christian lives and everyday world, social interactions, and somehow at least for me, I preferred the homilies addressing where they are at.

On a Sabbath, Jesus went to dine at the home of one of the leading Pharisees. The people there were observing him carefully. He told a parable to those who had been invited, noticing how they were choosing the places of honor at the table. He said; “When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not reclaim a table in the place of honor. A more distinguished guest than you may have been invited by him. And, the host who invited both of you may approach you and say, ‘Give your place to this man.’ Then you would proceed with embarrassment to take the lower place. Rather, when you are invited, go and take the lowest place so that when the host comes to you, he may say; ‘My friend, move up to a higher position.’ Then you will enjoy the esteem of your companions at the table for everyone who exalts himself will be humbled and the one who humbles himself will be exalted.” Then he said to the host who invited him; “When you hold a lunch or a dinner, do not invite your friends or your brothers or your sisters or your relatives or your wealthy neighbors in case they may invite you back and you have to repay them. Rather, when you hold a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind. Blessed indeed will you be because of their inability to repay you. For you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous.

If you were to walk out the doors of old St. Mary’s Cathedral and turn right, walking down Grant Avenue, you will soon discover dozens upon dozens of Chinese restaurants. That’s pretty obvious. Chances are you probably already knew that. What you might not know is that in most Chinese restaurants, the shape of the table is round. In most of them. That’s because in a Chinese banquet, that symbol of being round reminds us that this is in fact a meal and in that Chinese context any banquet the focus is on the community. But, there is actually a hierarchical dynamic to this as well. It might not be as explicit, but it’s there. If you are the host or the guest of honor in a Chinese banquet in a round table, you are seated on the chair that faces the door. Now this is slightly different than let’s say a traditional European model of a table setting. Think Downton Abbey, for example. In that setting, the table is rectangular and its long in which that shape emphasized hierarchy. In other words, it’s pretty clear who are the host and hostess, who they are. Right? Similarly—interestingly enough—what they both have in common whether it is Chinese or Downton Abbey meal—the guest of honor sits to the right of the host or hostess. I bring this up because every culture has their own set of rules of etiquette that signify at one level the dynamics between our relationship between one another, let’s call this the horizontal dynamics, what I would like to call, but it also signifies our relationship with the host and the relationship with the host to us. Let’s call this the vertical dynamics of any meal. What we heard in today’s gospel is similar dynamics going on, actually. This is 2000 years ago. Clearly we see the hierarchical dynamics at work. He is invited to the home of a Pharisee, someone who is pretty much up there. Jesus comes along and he notices all the different cultural norms of who gets to sit in these seats of honor. So, there’s a lot of hierarchical dynamics going on there. He does something pretty crass, actually and rude, he actually tells the host how to be a host by actually rearranging the seats. That would be like if I was invited by our Governor Gavin Newsome, by Gavin and Jennifer, and I went there to Sacramento to their mansion or wherever they live, and I came into their dining room and I began to rearrange the chairs myself. You don’t do this. He was doing it because normally when Jesus breaks the rules—and he breaks a lot of religious rules—it’s because it doesn’t mirror another meal or banquet that he has in his mind. That meal is what we call the heavenly banquet. The heavenly banquet. In the heavenly banquet there are different rules of etiquette, or different rules in general, that might not be applied in a Chinese restaurant or might be different than Downton Abbey or in Kenya, or in a Norman Rockwell painting. So, it is our task then to go out into the world, to proclaim this good news. To invite those people who are in the peripheries and in the boundaries of our society. To invite them to come to this feast of heaven and earth. To come to the feast where God remains the sole host. Christ remains the guest of honor. We go out, we invite them to come to this feast of heaven and earth, for God will provide all our needs. God will provide for all of our needs, we come to the table where God continually invites us—invites us to be one with all of us and one in the power of the Holy Spirit. Here at this table of plenty.

R1: Isaac Thomas Hecker was the founder of the Paulist fathers. An American, and a spiritual pilgrim. From his diary in 1843, Hecker prayed; “Now, O Lord, I ask in Jesus’ name, give to me more and more of your loving spirit and fill my whole being with your loving kindness.” I want to thank Paulist fathers Ricky Manolo and John Ardis and the staff here at Old St. Mary’s Cathedral who have helped us greatly during these past few days. In San Francisco’s ChinaTown, and for Sunday to Sunday, I am Father Mike Russo.